Processed with VSCO with s3 preset

Since Lucinda Williams discharged her first collection of unique melodies 40 years prior, she has pulled unfailingly sharp perceptions from her general surroundings, extending inside clash into an all inclusive condition. Her music has been elusive to arrange in light of the fact that she’s been so firm in her self-rule: She burned through the vast majority of the 1980s dealing with her milestone self-titled third LP, mixing rowdy blues with twanging nation, setting up an uncommon female foothold in the time’s stone scene. Her verses have gazed intently at harsh connections, broke relationships, and dusty streets, and they’ve advocated rebellion against abuse and the unmistakable tirelessness of being a lady in male centric limits. As such, at 67, she’s seen a ton she doesn’t have to endure.

Presently, on Good Souls Better Angels, her fourteenth studio collection, Williams evaluates the most recent of these revulsions: an organization dead set on revoking our freedoms. She reacts with ambiguous gruff power in her generally pressing and aggressive music in years: On “Man Without a Soul,” she’s brilliant with fury and scorn, singing, “You don’t carry anything great to this world/Beyond a snare of cheating and taking,” and cautioning this anonymous threat that his “mass of falsehoods” is descending. (It’s not frightfully difficult to induce who it’s aimed at.) “I invested a ton of energy composing these melodies from a position of being truly disappointed and irate about what’s been happening in the nation since we lost Obama,” she lets me know via telephone. “It’s noticeable all around. Many individuals are tired.”

Great Souls Better Angels likewise goes up against devils of Williams’ past, not simply her newsfeed. The tweaking “Wakin’ Up” addresses the confounding bunch of torment and legitimization Williams felt while in a damaging relationship years prior, and the collection’s focal point, “Large Black Train,” flips a typical figure of speech in blue grass music—a masterful train charging a way into the promising obscure—into a devastating similitude for approaching sadness. “Didn’t have a clue whether I was ever comin’ back/And I don’t wanna get locally available,” she sings mournfully, over trembling guitar. The impact is obviously helpless, a focus on a dull corner since a long time ago darkened. “I begin crying each time I sing it,” she says.

More Stories

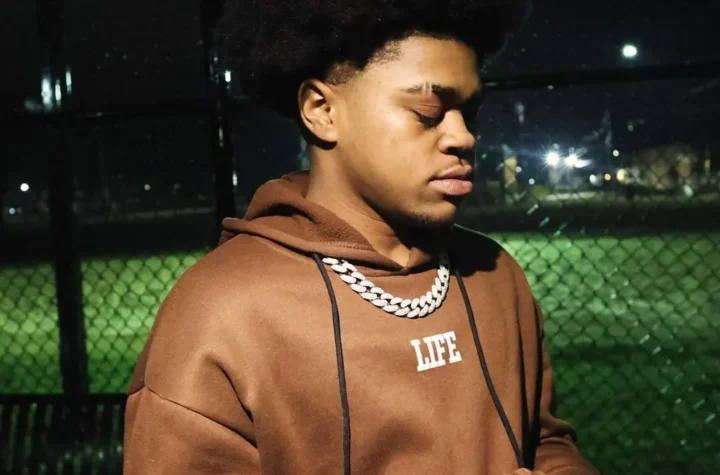

Fatlanski: DC’s Rising Star Drops a Summer Trap Anthem

The True Obi J: A Story of Resilience and Artistic Evolution

JU Da General: Rising from Chicago’s Streets to Hip-Hop Stardom