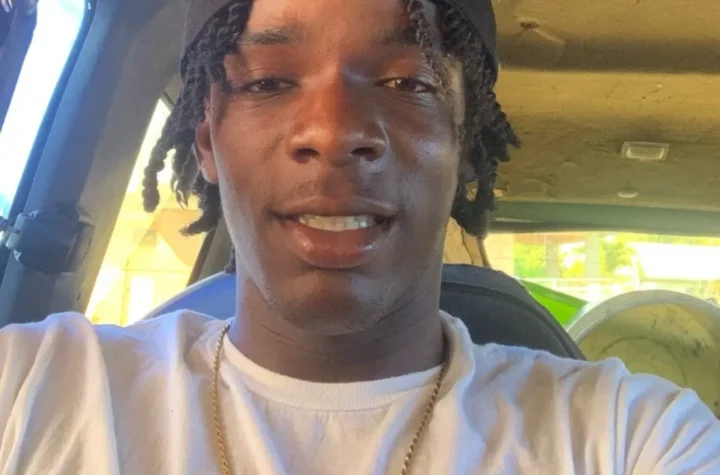

Medhane is thinking back about Future’s unapproachable mid-2010s mixtape run, when the Atlanta star apparently couldn’t sniffle without releasing another work of art. “That poo turned him up!” he says enthusiastically over Zoom. The 23-year-old’s theoretical, intelligent raps are unquestionably a long ways from Future’s supervillain regrets, yet he was enlivened by the hard working attitude. What’s more, in the course of the most recent a half year, the Brooklynite has been on a correspondingly productive tear with Own Pace, his inspirational advancement; oneself created Full Circle; and the current week’s Cold Water, his best collection to date.

On the new record, his sections check like fantasies hung together during a long metro ride, while the creation reviews the container burrowing beats of A Tribe Called Quest. At the end of the day: some New York crap. Medhane is an everyman, and his considerations are both individual and relatable, regardless of whether he’s rapping about discussions with his mother, escaping otherworldly trenches, or the significance of his locale. Cold Water is established in torment, yet it’s not sad. It’s a story about growing up that could resound with any dark child. “Everybody has their very own encounter,” he lets me know. “This is the place I’m at.”

Tuning in to his reflective tracks can here and there feel like a dreamlike intrusion of security. “Fourteen days in the medical clinic bed/Mind moving unusual/Crazy that I endured the year,” he raps in a dull stream on Cold Water’s “All Facts,” moving along without any more clarification. His verses are incredible in view of their nuance, in light of what’s forgotten about. You despite everything get it—in any event, when you don’t completely get it. His smooth beats, frequently civility of makers inside his very close imaginative network, help draw an obvious conclusion.

Medhane is essential for a continually developing grassroots development of specialists from New York and past, including Bronx rapper MIKE, Brooklyn aggregate Standing on the Corner, Chicago-reproduced artist KeiyaA, North Carolina’s Mavi, and Alabama’s Pink Siifu. “It shows the hoards behind the encounters of youthful individuals of color,” Medhane says of the scene. “It’s spread up until this point, and everybody has their own interpretation of it.”

Their people group is best spoken to at live shows, which can feel like family gatherings. Little, steadfast groups consistently make it out, regardless of if the presentation is being held in an appropriate setting, a dress store, or a yard. This previous November, Medhane performed at Brooklyn’s Cafe Erzulie, a personal social center point. During the show, the crowd assembled close, assisting with words that required additional accentuation. “It resembles strolling on a cut off tie/All them years I ain’t learn crap,” Medhane rapped that night, while the group, crushed so close that it was difficult to inhale, gestured alongside each word.

In any event, during a pandemic, his everyday hasn’t changed a lot. He’s still in his Park Slope den doing the standard thing: composing, recording, smoking. An amplifier floats behind him as we talk, and I hear the flick of a lighter as he gets some distance from the camera. There are a few workmanship pieces spread over the divider behind him, including an especially huge one with elephants that he copped from an African road celebration. “We’ve been isolated before isolate, in here workin’,” he says, the words seeming like a continuous flow line from one of his tunes.

Medhane-Alam Olusuola was brought up in the core of Brooklyn, between his mom’s home in Bed-Stuy and his dad’s in Prospect Heights. Like any individual who experienced childhood with the web, his melodic craving is shifted. His developmental impacts incorporate everybody from individual Brooklynite Biggie Smalls to Chicago’s drill envoy G Herbo to chattering London crooner King Krule. He originally found out about Gil Scott-Heron, a significant motivation, in the wake of hearing the amazing artist and performer’s collection with electronic maker Jamie XX. “I even have a video of me doing the cooking move to Lil B’s ‘Suck My Dick Hoe,’” he says, somewhat mimicking the move.

He spent a lot of his adolescence and adolescent years as an aspect of the Ifetayo Cultural Arts Academy, which expects to engage children of African drop. There, he rehearsed and deepend his association with human expressions, offsetting it with a serious spotlight on his homework. From the get-go, Medhane skirted two evaluations. “In first grade, the educator thought my mother was doing all my schoolwork,” he recalls. (She wasn’t.) He proceeded to go to NEST+m, a profoundly particular open secondary school in Manhattan that has some expertise in encouraging STEM abilities. He exceeded expectations, graduating at 16. Following a hole year energized by his mother, he selected the broadly perceived structural building program at Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Mellon University in 2014.

Medhane’s association with hip-jump developed close by his instruction. With the arrival of 2015’s Grays in Yellow, a venture made close by maker Slauson Malone under the Medslaus moniker, Medhane started to pay attention to rap. It got hard for him to come back to school in the mid year of 2017, as his similarly invested network made their mark with discharges like MIKE’s May God Bless Your Hustle and Standing on the Corner’s Red Burns. “In any case, I resembled, ‘On the off chance that I don’t complete school, my mother is going to take a gander at me insane,’” he says. There were times when he plunged out for a show, however: Once, in the fall of 2018, he took off on a Thursday night to rap in London and was back in Pittsburgh for class on Monday morning. “That poop spun me, brother, I was truly messed up. I was simply managing individual issues and feeling distraught discouraged,” he picked, his words cautiously. “‘I truly gotta return to class after this?’”

After his come back from London, Medhane had a breakdown. He took a rest from recording and invested the majority of his energy marathon watching The Wire. He went to treatment once while at school, however never returned. After he graduated the previous spring, Medhane’s grandma skilled him and his cousins an excursion to Kenya, utilizing cash she had set aside. It was the revive that prompted his ongoing innovative overflowing.

“My grandmother experienced childhood in the Coney Island ventures—she had kin dependent on heroin—and she’s accomplished such a great deal in her life,” he says, sounding somewhat exasperated, similar to it’s difficult to get the words out. “In Kenya, I was taking a gander at the skyline with my family and simply resembling, ‘Yo, everybody has their own injury and emotional well-being issues.’ I put it into setting, seeing what my family has survived, and what individuals of color have survived. In the event that they can do that, I can as well.”

More Stories

TLE RO – Bessemer’s Next Big Voice in Hip-Hop Drops “Stand Firm” Ahead of Mama’s Lil Steppa 2

UberPack Is Next Up: Detroit’s Pain-Turned-Poetry Rap Phenom

Spazz Gee: The Visionary Hip-Hop ArtistRedefining the Sound of Las Vegas